Death on the Ferry: The Alton Collier Story

On April 27th, 1946, an African American resident of Coronado and employee of the famous Hotel del Coronado, boarded an 8:20 pm ferry to San Diego. A racist attack on board ended in his death.

Updated April 26, 2024

IMPORTANT UPDATE: Alton Collier’s death has now been recognized as a “racial terror lynching” by the Equal Justice Initiative. Mr. Collier's name has been added to the list of racial terror lynching victims in their records and will soon be commemorated at the Legacy Sites in Montgomery, Alabama. Alton Collier is the third victim of racial terror lynching thus far documented by EJI who was killed in the state of California between 1865 and 1950.

A group of Coronado and San Diego residents have subsequently formed a Community Remembrance Coalition and will conduct a Remembrance Event in honor of Alton Collier in the late Spring 2024.

Alton Collier’s Early Life

Alton Collier was born in his parent’s sharecropper farmhouse just outside of Luling, Texas, in 1920. Alton was among the nine Collier children who divided their time between working in the cotton fields and attending school in segregated Jim Crow Luling.

When Alton was eight years old, his father Rufus died of pellagra, a debilitating disease caused by a vitamin deficiency due to malnutrition. Pellagra had quietly killed thousands of impoverished rural southerners in the same period. Alton dropped out of school after sixth grade to help his widowed mother on the farm and to care for his younger siblings.

In 1938, at age 18, Alton joined a New Deal program, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). Over a period of 18 months at the CCC, traveled to various works sites in Texas and Arizona and learned a variety of trades, including cement work. It was while working for the CCC in 1939 that Alton met 17 year-old Georgia Crawford, a student who was also participating in a New Deal Program, the National Youth Service.

Alton would leave the CCC in 1939 travel south to Corpus Christi, Texas, where he began work as a construction laborer doing cement work for the Brown and Root Company, which had the contract to build the new Naval Air Station in Corpus Christi. When Georgia finished her program at the National Youth Service in 1941 she would travel down to Corpus Christi, where the young couple would marry on October 31, 1941. During this time, Alton registered for the Draft, but was later rejected due to his chronic asthma.

The young couple lived at 2202 Marguerite Ave with Alton’s brother Ural. Georgia also spent nights living in the servant quarters of her employer, Navy Lieut. Dr. James E. Dailey, where Georgia worked as a live-in maid. In February of 1944, Lieut. Dailey was transferred to Naval Air Station (NAS) North Island in the small island town of Coronado, just across the Bay from San Diego. Georgia and Alton jumped at the the opportunity to join the Dailey family in Coronado, where Georgia continued her work for the family in as a live-in maid in their home at 1114 G Avenue. Alton was allowed to live with Georgia in the Dailey home, but Georgia was deducted $10 a week from her salary as a tradeoff for Alton staying with her.

Life in Coronado

Once in Coronado, Alton immediately found employment as a cement worker at NAS North Island, but would eventually leave that employer in late 1944 or early 1945 and begin work for The Hotel del Coronado, where he did cement finishing work (as a Union member of the American Federation of Labor), making $1.85 an hour.

In early 1945, Lieut. Dailey was transferred, forcing Georgia and Alton to briefly move to San Diego, where they lived on Island Ave, near downtown. Alton continued his cement work, traveling by ferry daily to his job in Coronado, while Georgia worked at nearby Hillsdale Hospital.

Around September of 1945, Alton and Georgia moved back to Coronado, as a result of Georgia getting work as a domestic live-in maid for Navy Capt. Herbert A. Jones (ret.) and his wife Ethelyn at their home at 727 Alameda Blvd. Alton continued his work for the Hotel del Coronado.

The Jones family were well known and respected in Coronado. Capt. Jones (ret.) and his wife Ethelyn lost their only son, war hero Ensign Herbert C. Jones, during the December 7th, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor. Ensign Jones was posthumously awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor in 1942 for his bravery in action on that fateful day.

April 27, 1946 - The Ferry Incident

At approximately 7:50 pm, on Saturday, April 27th, 1946, Alton left his wife Georgia (who was still working until 9 pm) at home at 727 Alameda Blvd and walked a few blocks to board a street car for the Coronado Ferry Landing. According to his wife Georgia, Alton was heading to San Diego on quick roundtrip mission - to pick his newly tailored trousers and Georgia’s new topcoat at Ferris’s Department Store downtown and return back to get Georgia to go see Count Basie at The Cotton Club (newspaper records indicate it was more likely that it was pianist Earl “Fatha” Hines playing at the Cotton Club, not Count Basie) . Alton arrived at the ferry landing around 8 pm and after paying for his ticket, climbed up the stairs to the pedestrian seating area with the other passengers as a steady flow of cars pulled aboard the ferry into their allotted positions.

Alton had boarded the ferry named “Coronado,” one of four auto-ferries in operation between Coronado and San Diego at the time, and comprised an important lifeline for Coronado prior to the arrival the Coronado bridge. On Saturday evenings like this, the ferries provided an easy connection to the department stores, restaurants and nightlife across the bay, and were a popular option for military personnel based at the local NAS North Island base.

The bottom level of The Coronado was exclusively reserved for cars, while the mezzanine deck was meant for pedestrian passengers. This level had a central enclosed seating area with outdoor terrace decks on the port and starboard sides of the vessel which extended to the outer edges of the ferry and were about twelve to fifteen feet above the water. The top level was reserved for crew, and had two opposing Captain’s bridges or wheelhouses at the bow and the stern.

According to Coronado and San Diego news accounts of the incident, approximately 30 passengers boarded this ferry with Alton Collier and were mostly Navy personnel, including two officers. Two of these sailors were 19 year old Freddie Leroy Johnson and 19 year old Otis Reed Gilbert, both Naval Reservists, and like Alton Collier, also from Texas.

Johnson and Gilbert had met while deployed on the USS Leedstown, and the two native Texans had become close friends (The USS Leedstown would later be decommissioned in Seattle, Washington, in March of 1947). At the close of the war, the two men were soon transferred to San Diego attached to the USS Charles Badger and were stationed at NAS North Island as they awaited their next deployment.

Local news reports indicated that The Coronado departed the Ferry Landing at approximately 8:20 pm. According to Coronado and San Diego news accounts of the incident, soon after departure, Alton Collier became engaged in a heated argument with Johnson and Gilbert, and at some point Alton Collier drew a knife and slashed Johnson on the arm and shoulder. It was then reported that Gilbert confronted Collier with two boat hooks which police say prompted Collier to leap over the fifteen foot high railing into the Bay. Collier was reportedly to have screamed for help after he hit the water. The Coronado briefly stopped and an unmanned life boat was placed into the water. Then, inexplicably, the Coronado proceeded on its way to San Diego to drop its passengers. After reports of the incident reached Coronado, a number of police lined the shore in case Collier made it ashore, but he never did. Naval crash boats and Coast Guard boats joined in the search the following day.

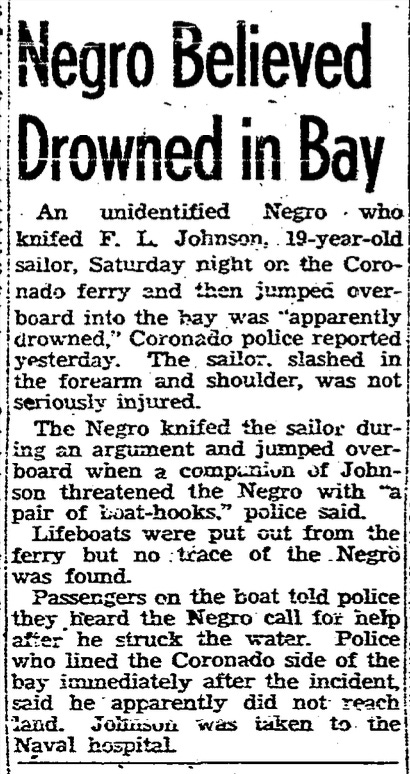

The first account of this incident appeared in the San Diego Union on April 29th:

Back at their small servant quarters room at 727 Alameda Blvd, Georgia Collier had a sleepless night. Alton had not made it home as agreed, which was not like him. On Sunday morning she took the Ferry across the Bay to San Diego and asked the local police and hospitals if they had anyone there named Collier. She eventually made to a friends house and went out to a movie to get her mind away from her worries. She reached Coronado late that evening. On Monday morning, April 29th, she woke up early and went to the Coronado Police Station to enquire if they knew anything about her missing husband. Officer Green told her that a Black man had been “pushed” and “shoved” from the Ferry into the water and asked if she could identify a pair of glasses that belonged to the man. They were Alton’s. She knew Alton couldn’t swim, and in that moment knew that her husband was gone.

Mrs. Collier immediately suspected foul play and demanded the Coronado and San Diego Police investigate the case. She must have been in a terrible state of trauma as she was forced to travel by ferry to meet with the police in San Diego. To her shock and dismay, both cities claimed they lacked jurisdiction to conduct an investigation as the “accident” happened in a “no-mans land” in the middle of the Bay between the two jurisdictions. There was nothing they could do.

After six days of inaction from police and Alton’s body still missing, Georgia Collier called upon the law office of highly respected African American lawyer Walter Gordon in his Los Angeles office on May 3rd. Gordon quickly assembled a team of two lawyers to travel to San Diego and assist Ms. Collier in her efforts to press for an investigate into the matter.

The Body is Found

On May 4th, a week after the incident, Alton Collier’s body washed ashore on North Island, Coronado. The San Diego Union printed the story below on May 5th, and referring to Collier as the “suspect.”

In that story, Coronado Police Chief June Jordan suggested that there were several points to the story from the two young sailors, Johnson and Gilbert, that “lacked clarification.” He requested that any witnesses who had information to contact the Coronado Police Department.

On the day the body was discovered, surgeon Dr F. E. Toomey conducted the initial autopsy of Alton Collier and determined the cause of death to be “drowning.” San Diego Coroner Chester Gunn announced that a Coroner’s Inquest would take place the following week.

Incredibly, despite the announcement of a Coroner’s Inquest (also known as a Coroner’s Jury), Coroner Gunn issued a death certificate on May 8th, which indicated the cause of death to be asphyxia by drowning and that the incident was not an accident, nor a homicide but “Suicide.”

Several days later the weekly Coronado Journal provided further confirmation of the upcoming inquest and other important facts related to the case, including the fact that Otis Reed Gilbert was being held in the Navy brig pending the completion of the investigation being conducted by the Coronado Police Department (note: a FOIA records request to the Coronado Police Department for records was unsuccessful as CPD reported they had no records on file for the incident).

Despite the “points” noted by the Coronado Police Chief that lacked clarification, and that Gilbert was in the brig, or that a Coroner’s Inquest was going to be held, the dominant narrative of this tragic case in both the weekly newspaper in Coronado and the major dailies in San Diego was the same. The real “suspect” was a Black man who was involved in a scuffle on board the evening ferry and had slashed a sailor. When this slashing assailant, Alton Collier was confronted by a group of sailors, he chose to vault over the railing of the ferry in the darkness of night, falling nearly fifteen feet into the bay, and drowned. The Coroner declared this leap to be a willful and successful act of suicide.

At no point did any of these newspapers ever attempt to humanize Alton Collier. The papers never mentioned Alton had a loving wife named Georgia Collier, or that he was a worked for nearly two years as a union member and employee of the famous Hotel del Coronado. Her voice in this story would have helped concerned citizens understand what kind of person Alton really was. She would have explained that it was not in the nature of her mild-mannered, bespectacled husband to attack anyone. She could have explained that her quiet, gentle husband could not swim, had never been in a fight in his life, more did he own or carry a pocketknife. She would also attest that he would never be so foolish as to leap fifteen feet into the darkness of night into the San Diego Bay, nor would he commit suicide. Her voice was silenced because it did not fit with the narrative of a violent black man who had attacked two patriotic Naval personnel.

The Southern California Black Press sheds new light - describes a racist attack and cover-up

The case was covered by the Black Press quite differently. The first story from the Black Press appeared on March 11th in the Black-owned San Diego newspaper The Lighthouse:

The most prominent article from the Southern California Black Press appeared on May 16, 1946, soon after two lawyers from Walter Gordon’s Los Angeles law office had returned to Los Angeles from their time in San Diego and Coronado, where they had been requested by Georgia Collier to investigate. Gordon had dispatched two seasoned African American lawyers to San Diego, Roger Q. Mason and former US Army Capt. Everette M. Porter, a Los Angeles lawyer who had just recently returned to civilian life after three and a half years in the South Pacific during WWII. Mason was a member of the bar from Dallas, Texas and the head of investigations for the Gordon firm. Capt. Porter’s unique status as a war veteran and former officer would have been helpful in gathering information in a case involving military personnel, while Mr. Mason’s Texan roots would have also been helpful in a case where all involved were Texans.

Porter and Mason shared their disturbing findings with Charlotta Bass, the influential owner and editor of Southern California’s largest African American weekly newspaper, The California Eagle. (The remarkable Charlotte Bass had been a staunch defender of Civil Rights in California for decades and would later become the first African American woman to run for Vice-President of the United States in 1952, as part of the Progressive Party ticket).

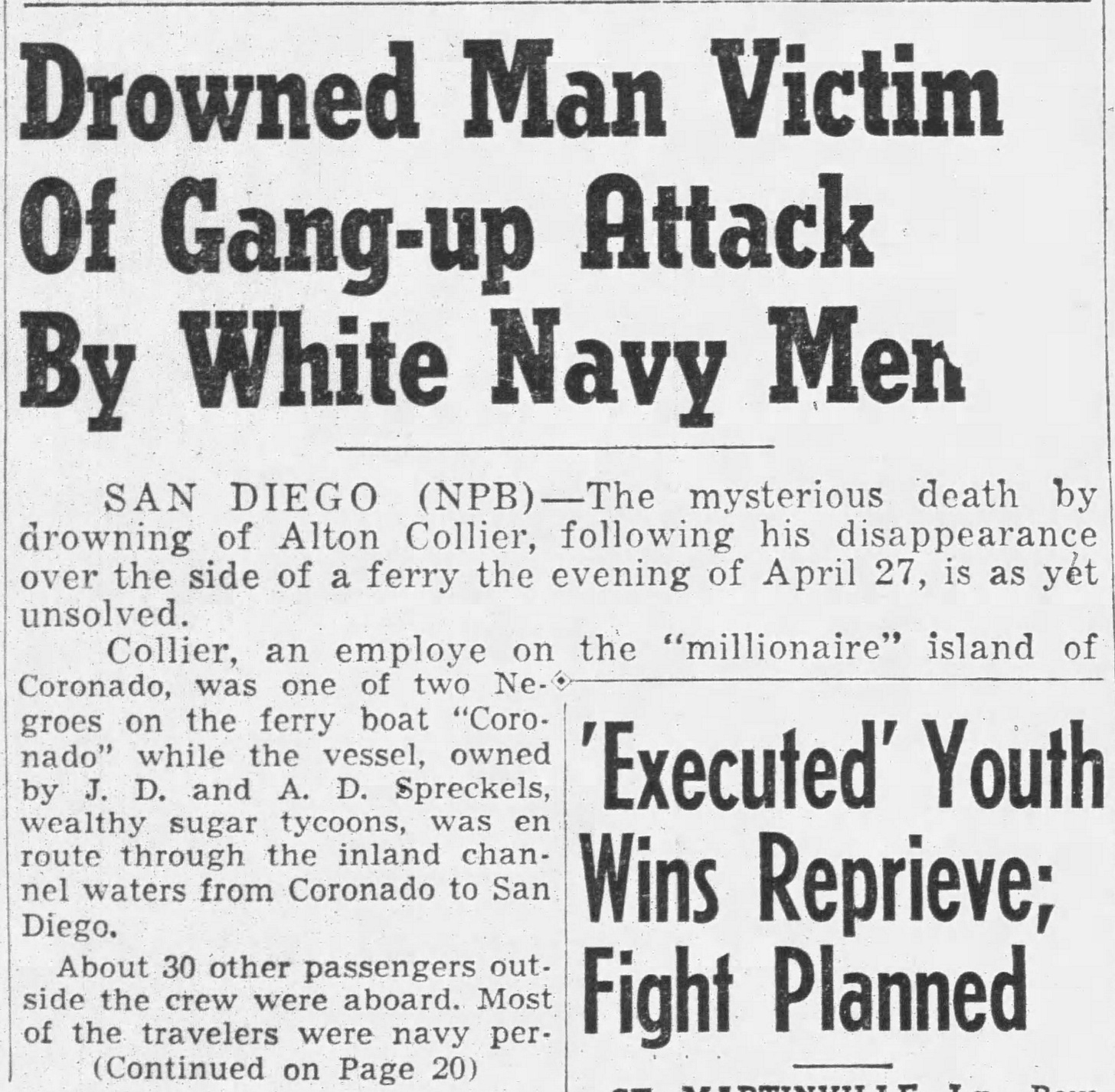

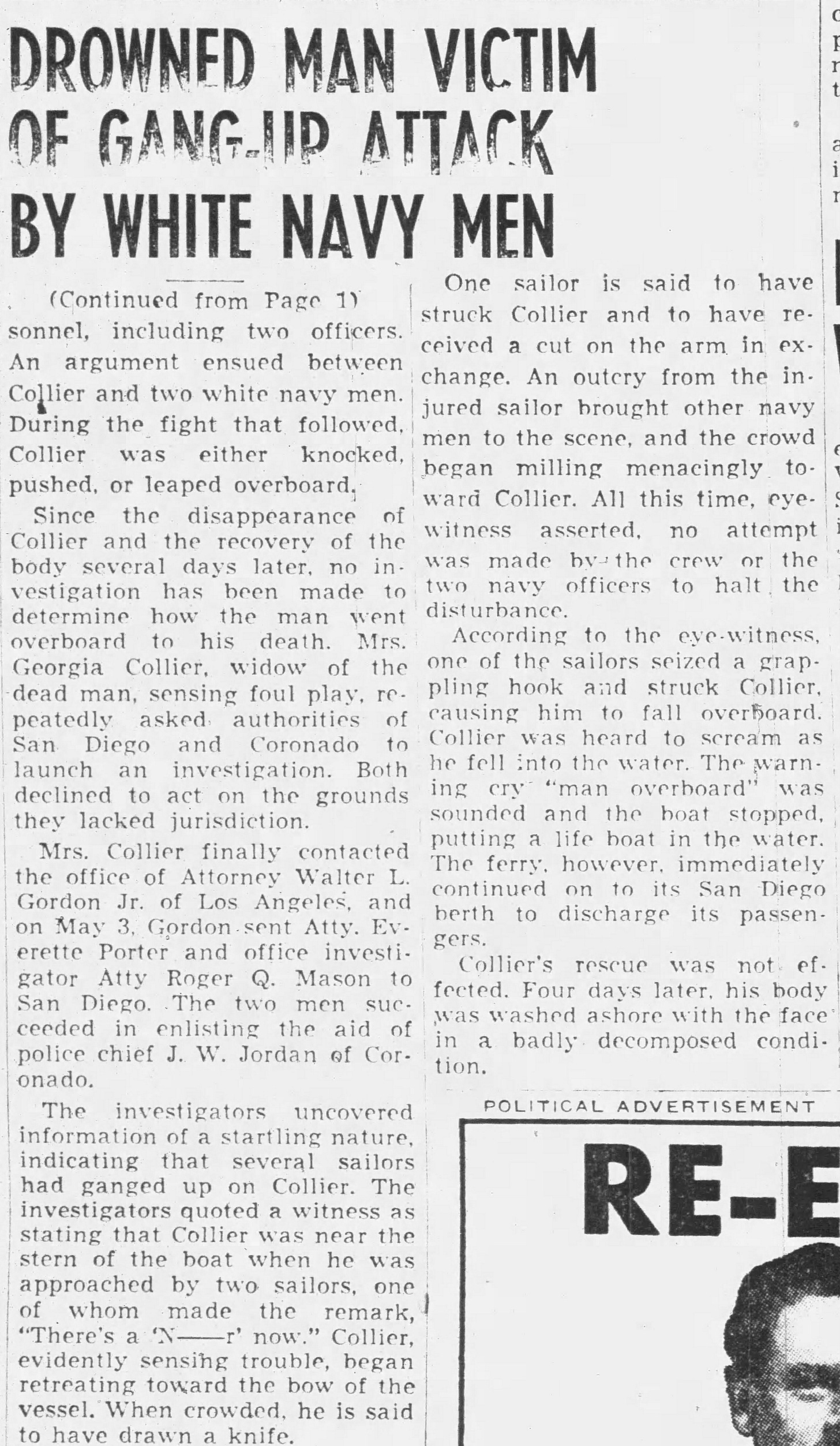

The following headline story of the Collier case appeared on the front page of the Eagle. It certainly presents an alternative narrative of the incident.

The story made clear that Collier was targeted by his race by the sailors who taunted Collier by shouting “There’s a N——r now!” and pursued him as he tried to avoid confrontation by moving to another part of the ferry. Once cornered Collier is said to have defended himself with a knife and slashed one of his attackers (though a knife was never found or presented as evidence). Reportedly, other sailors sounded the alarm and surrounded Collier. At no time did the two Naval officers on board and the Ferry operators intervene. One sailor is said to have then used a grappling hook to knock Collier overboard, who screamed for help as he was falling into the Bay. The boat stopped briefly and unloaded a life raft, and then continued on its way to San Diego.

The Investigation Ends

On May 16th, the San Diego Evening Tribune reported that the Coroner’s Jury made their final determination that the death was by accidental drowning, effectively closing the case. A copy of the original file covering Alton Collier’s autopsy and the result of the inquest was recently obtained from the San Diego County Medical Examiners Office. The page that refers to the inquest is below:

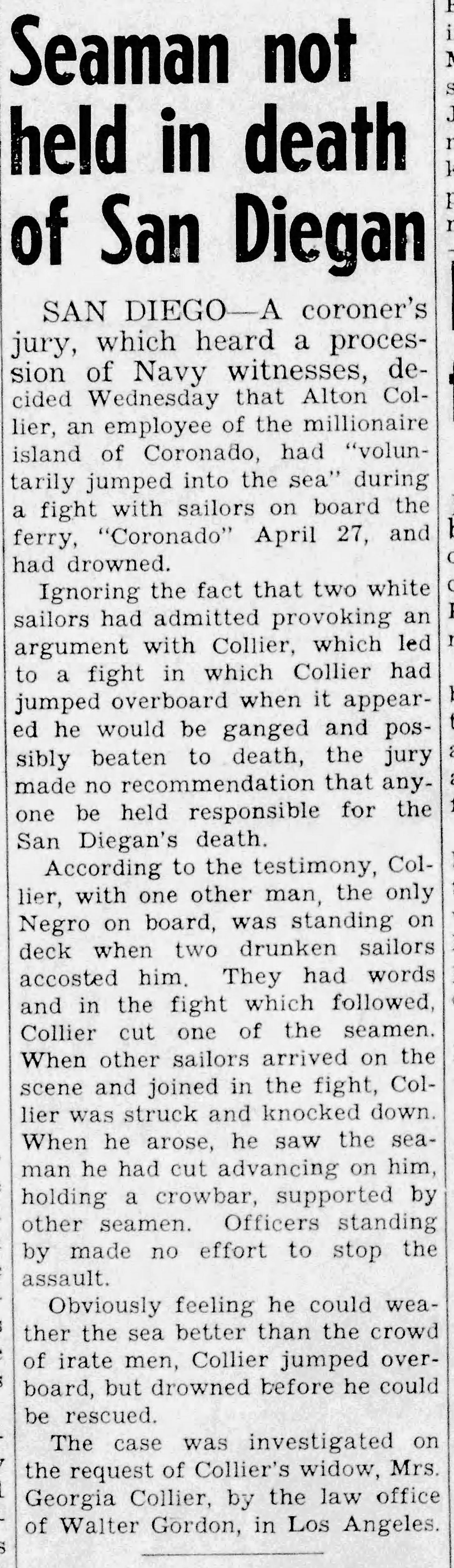

Yet again, a more compelling story of injustice was printed in the Black Press. On May 18th in the Black- owned Los Angeles Tribune the following story was run:

After the ruling, Georgia Collier brought the body of her husband Alton Collier back to Luling, Texas, for burial.

On May 21st, Otis Reed Gilbert and Freddie Leroy Johnson were added to the roster of the USS Riley, and departed San Diego. Shortly thereafter they were released from the US Naval Reserves with honorable discharges on July 16th. They were both back home in Texas soon after.

Soon after arriving back in Texas, on August 18th, Otis Reed Gilbert married Maretta Collier (whose surname bizarrely matched that of the man he had just months earlier tossed off a ferry to his death).

A Widow continues her fight for Justice

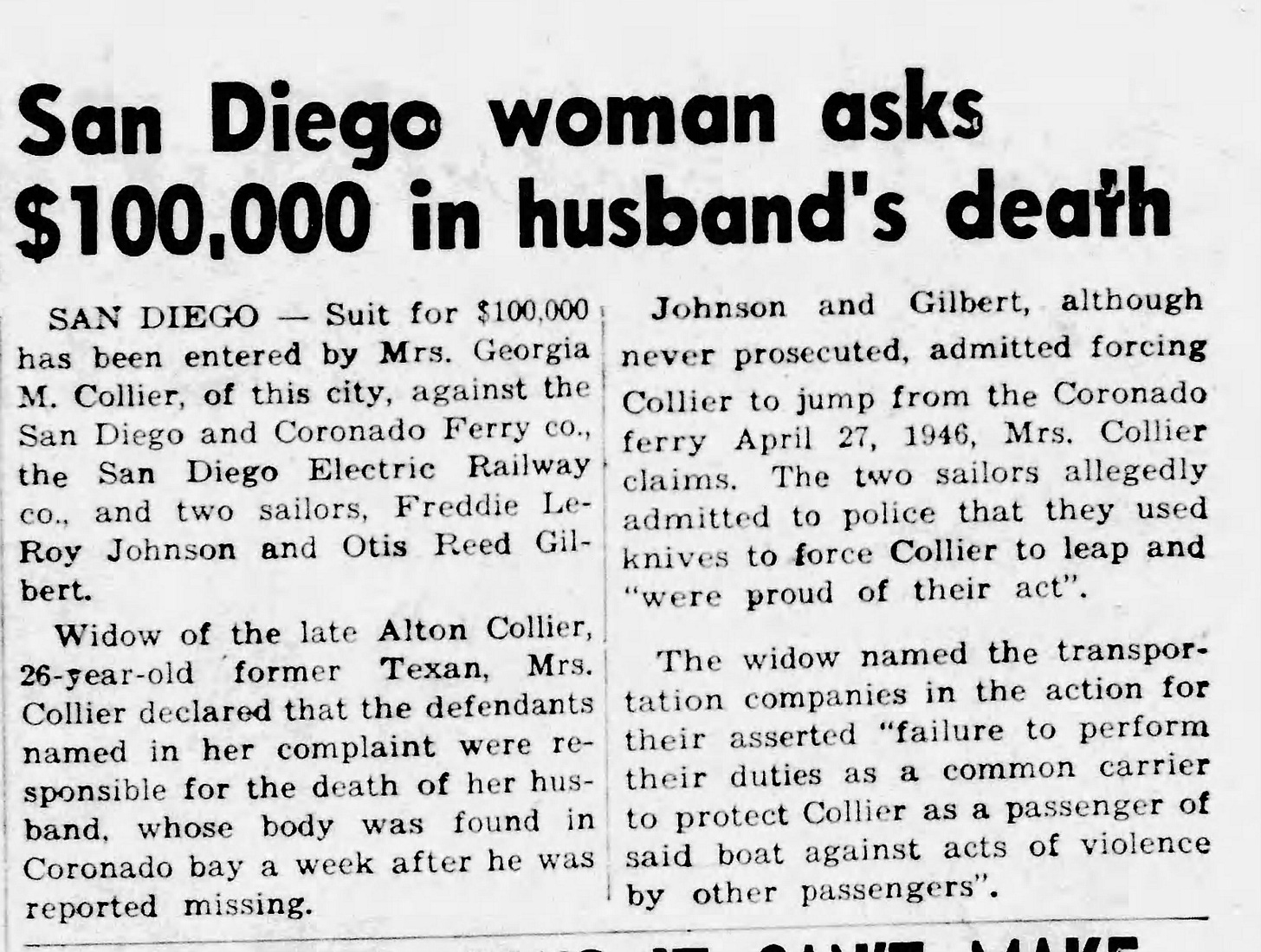

On April 22, 1947, nearly a year after her husband’s death, Georgia Mae Collier, filed suit in San Diego Superior Court, suing The San Diego & Coronado Ferry Co., The San Diego Electric Railway Co., Otis Reed Gilbert and Freddie Leroy Johnson. The story below is from the April 22, 1947 edition of the San Diego Union Tribune:

Interestingly, an additional story on the lawsuit appeared nearly five months later in the Black-owned Los Angeles Tribune of September 6, 1947:

Her lawyer, Rollin L. McNitt, was a towering figure in Southern California legal circles. He had been Dean of Southwestern School of Law between 1920-1940, and was the powerful Chairman of The Los Angeles County Chapter of the Democratic Party. In late May of 1948, he inexplicably amended the original complaint with a change that could only appear to be explained as sabotage or malpractice, which caused the case to be dismissed on July 1, 1948 “with prejudice as to all defendants.” Certainly not coincidentally, just a few days later, the San Diego Electric Railway Co. and the San Diego & Coronado Ferry Co. was sold to Jesse Haugh for $5,500,000.

A full copy of this important case file was located on March 26, 2024 which resulted in this original story being updated on March 27, 2024. The full case file, which includes a remarkable 50 page deposition of 24 year old Georgia Collier, can be found here: Georgia M. Collier vs. San Diego & Coronado Ferry Co., 1947

Soon after the case was dismissed, in 1948, Georgia Mae Collier would marry Dearmon Crayton. In 1950 she was listed in the Census as working as a nurse at Golden State Hospital. She later divorced Dearmon and eventually remarried in the late 1970s and became Georgia M. Sewell. Georgia Sewell passed away in Torrance, California in 1988 at the age of 66.

Otis Reed Gilbert, one of Alton Collier’s assailants, committed suicide at age 31. He was found in a hotel room with a gun in one hand and a court letter next to his body detailing a restraining order from his wife as part of a divorce proceeding. Freddie LeRoy Johnson died in Texas in 1998.

In 1969, the Coronado Bridge was completed, and on August 2nd, Jesse Haugh, President of The San Diego and Coronado Ferry Company, officially ended the 83 year era of the auto ferry between Coronado and San Diego, and decommissioned the Coronado.

Reckoning with the Past

Alton Collier’s life was taken on April 27, 1946 in an act of targeted racist violence. The perpetrators of his murder never faced criminal charges.

According to the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) between the years 1877-1950, 4,400 African Americans were lynched as part of an ongoing campaign of racial terror against African Americans in this country. According to EJI, “of all lynchings committed after 1900, only 1 percent resulted in a lyncher being convicted of a criminal offense.” In addition, EJI’s “research confirms that many victims of terror lynchings were murdered without being accused of any crime; they were killed for minor social transgressions or for demanding basic rights and fair treatment.”

What is a Racial Terror Lynching? - Bryan Stevenson of EJI

While Alton Collier’s death does not fit the commonly understood characteristic of a racist lynching involving a rope and a tree, it is worthy of examination. Mr. Collier was targeted and ultimately lost his life because of his color and for defending himself. All African American men in that period of American history, particularly those like Alton Collier from rural “Jim Crow” South, knew very well that if you ever looked or said something that caused offense to a white person, or happened to be randomly caught up in the wrong place at the wrong time, you could be the victim of racial violence, including lynching.

Alton would have also been taught and learned firsthand in Texas that if he fought back against any white man, particularly a group of white men, he also would be risking his life. He would have likely recognized in their voices that these boys on the ferry were Texans or Southerners, who had grown being taught those same rules. The fact that Alton may have eventually chose to fight back only further confirms that he believed he was in grave danger of being thrown into the dark waters of the San Diego Bay and had no choice but to fight back. We also know from Georgia Collier’s deposition, that her husband did not own or carry a pocketknife.

This was a racially targeted altercation that ended in the death of Alton Collier, and the justice system failed to bring charges against the assailants who caused his death. Instead, Alton Collier was portrayed as a violent assailant, who inexplicably chose to take his own life by vaulting into bay.

Unlike the majority of lynching victims in the United States, Alton Collier did not die by falling from a tree with a rope around his neck, but rather tossed overboard from a ferryboat into the dark waters of San Diego Bay.

This tragic story did not happen in a rural Texas backwater. It happened here in Coronado, California, to a Coronado resident, just a few hundred yards from shore.

Kevin Ashley, Coronado, original story appeared April 27, 2023, and updated on multiple dates.