Coronado's Hidden African American History

A brief introduction to Coronado's forgotten African American history and the Crown City's pioneering African American families.

I began my research into the history of the African American community in Coronado almost by chance, in February of 2020. My son’s Coronado High School (CHS) basketball team was preparing to play for the California Interscholastic Federation (CIF) Division 3 Championship that year, and I was immensely proud of him. We had moved to Coronado from Kenya in 2016, and basketball had been key to his sense of belonging at Coronado High, which is a predominantly white school (Kieran was one of two African American players on the team).

The team had only won two CIF championships in its long history, the first title being won in 1956. Being both a basketball fanatic and a history buff, I felt it necessary to research more about that first team and its journey to the title. I never imagined that this simple research would be a game-changer for me and set the stage for the creation of The Coronado Black History Project. That search led to the discovery of this photo of the CHS 1956 CIF championship squad:

I was immediately surprised to note that three of the nine players were African American; I had assumed (wrongly) that Coronado was a white enclave back then. I was already knowledgeable about the fact that many neighborhoods and cities in Southern California had historically utilized racially restrictive covenants and discriminatory practices known as “redlining” in order to keep African Americans out. I had assumed Coronado might have been one of those places which would have kept African Americans out.

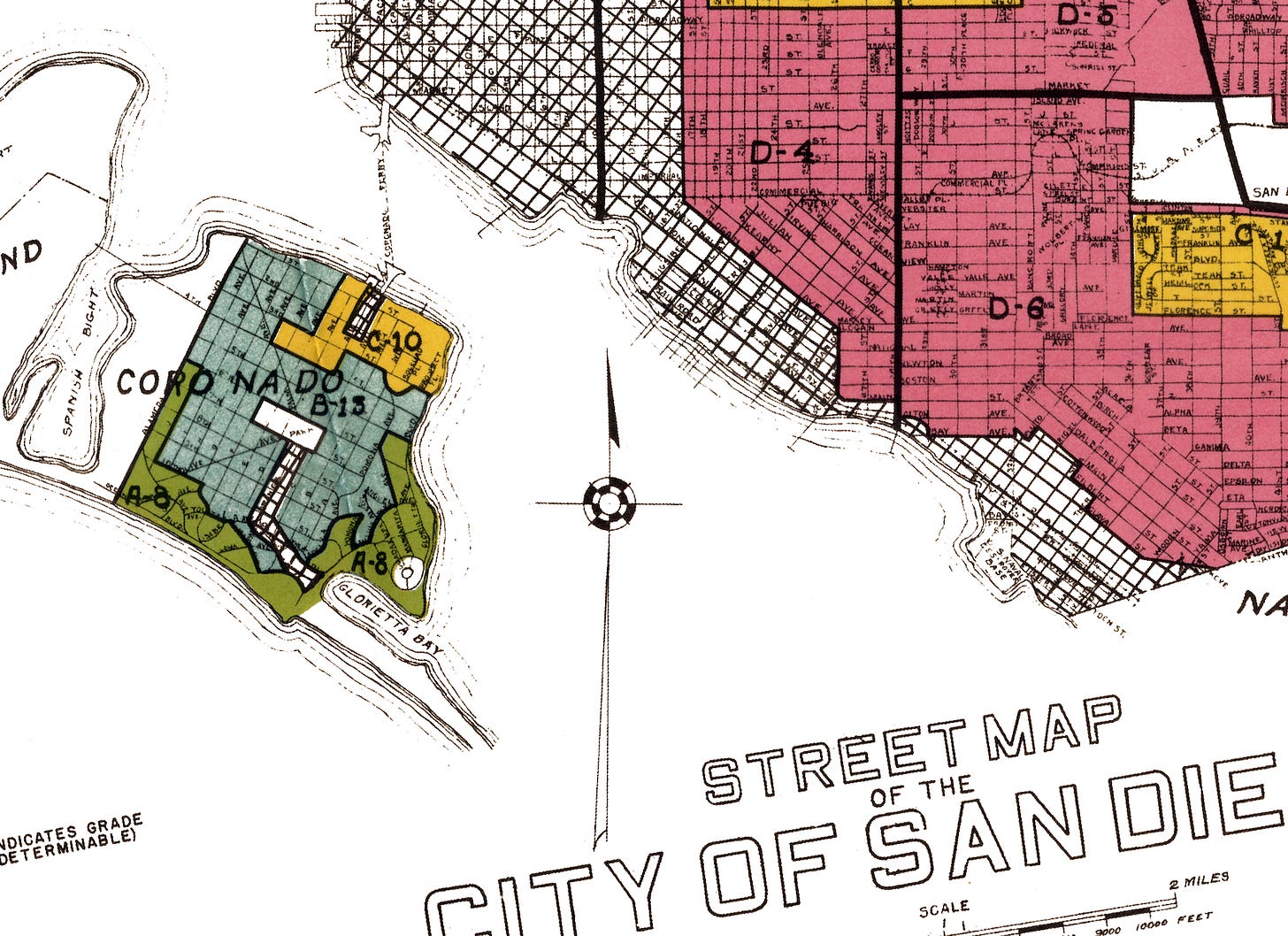

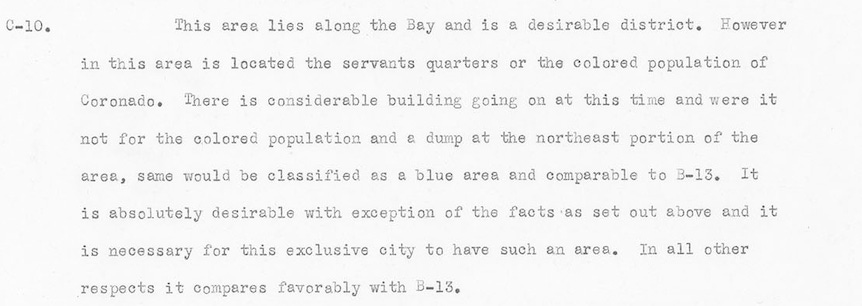

I went back and reviewed the Federal Government’s Home Owners' Loan Corporation “redlined” map of 1938 for San Diego and Coronado, as well as the description of the C-10 neighborhood in Coronado (see below). The description confirmed the presence of African Americans in Coronado as far back as 1938 (an important fact in itself), but it also reflected the blatant racism prevalent at that time:

I would later discover that the redlining and use of restrictive covenants that I had suspected did in fact occur. However, it turns out that the boys on the 1956 team did not live in the “village” section of modern day Coronado. They actually all lived in the Federal Housing Project on Mullinix Drive (near present day Tidelands Park), where nearly 25% of the city’s population lived in 1956.

Federal Housing Project, 1946-1960s

The Federal Housing Project were a cluster of large apartment blocks comprising nearly 750 apartment units, built by the government at the end of WWII. Due to labor shortages on base, the apartments housed both enlisted men and their families, as well as civilian employees and their families. In 1956, it was in these Federal Housing Project apartments that lived between 400-500 African American residents, about 20% of the total Housing Project residents, and nearly 5% of the population of Coronado.

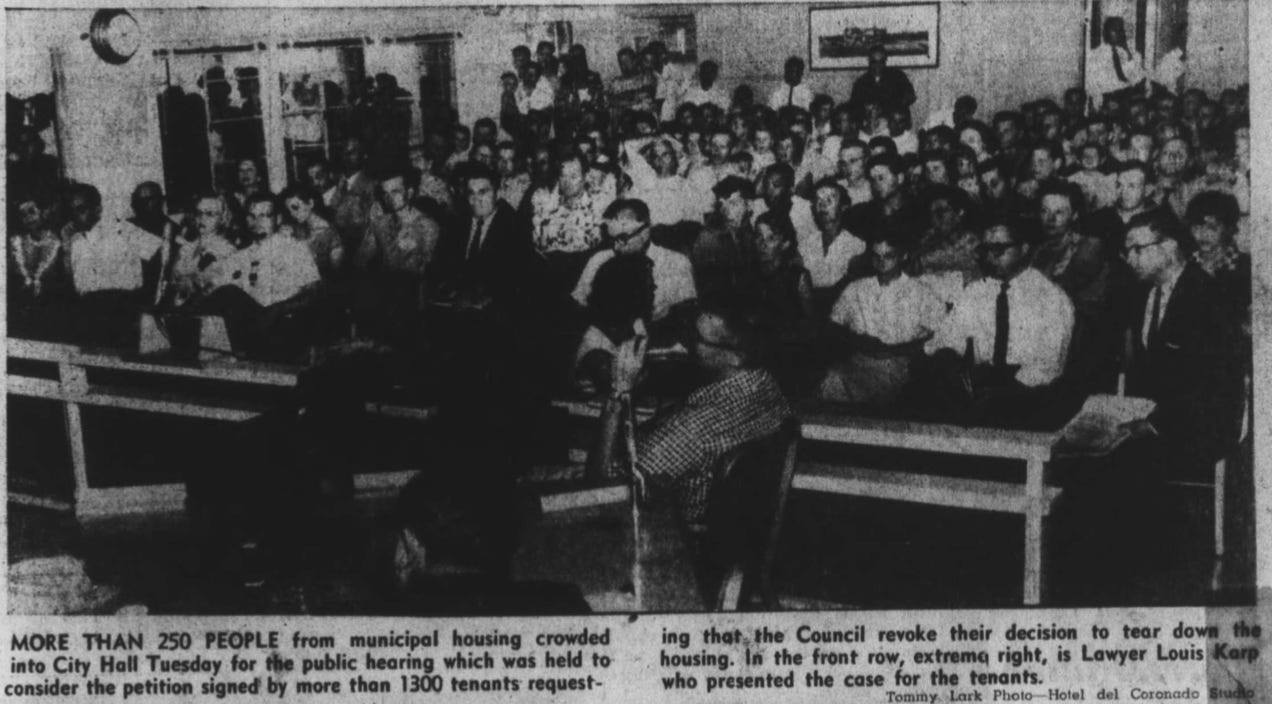

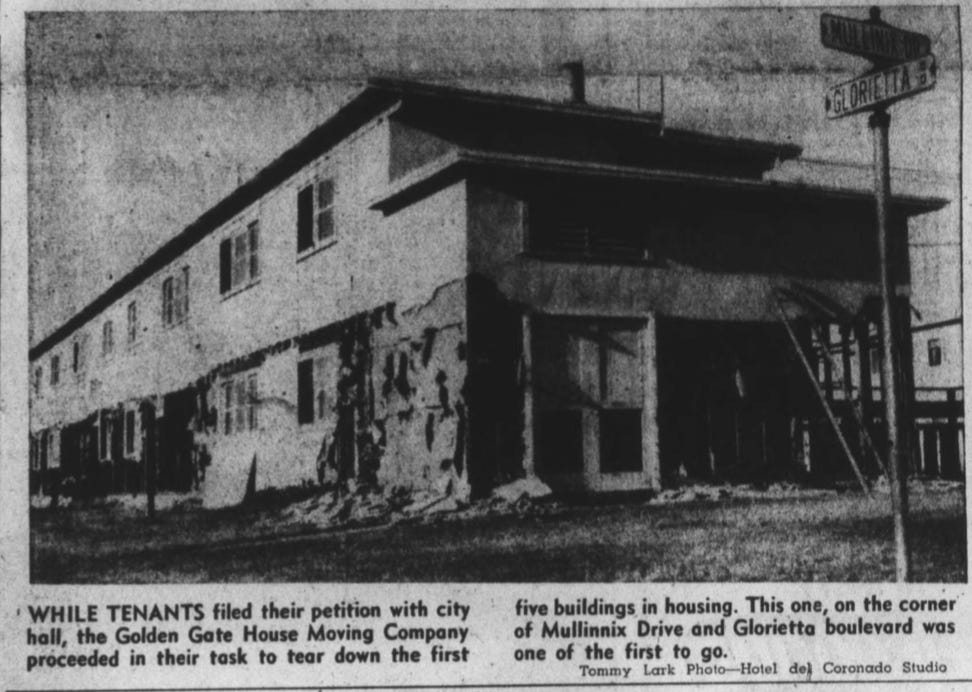

The city took over the apartments from the Navy with the promise that they would not tear them down. The city broke their word and in June 1957 and began tearing down a portion of the apartments, displacing some of the residents. The Navy, in a rare move, allowed their service members to attend an upcoming City Council meeting to raise their concerns about the eminent demolition of the remaining housing. A large portion of the housing was then allowed to remain until the 1960s, when the remainder were demolished. Several former residents of these apartments in the late 1950s and early 1960s confirmed that the apartments were extremely diverse, with many White (European), African American, Filipino, and Hispanic residents. Many felt they were treated as second-class residents by “village” residents of Coronado.

Historical Memory

A big contributor to my original ignorance of the existence of Coronado’s African American history was the current complete lack of any visual evidence on display of African Americans in our historic town. Among the many historic black-and-white photos displayed publicly around Coronado, not one contains an African American. This includes photos displayed throughout the walls of the Hotel Del, on the “Imagine Tent City” commemorative installation on the Glorietta Bay Promenade near City Hall, within City Hall itself, or at the Coronado Historical Association Museum. What is on display is an abundance of historic photos of White employees, tourists and residents. The image portrayed (though perhaps unintentional), is that of a “whitewashed” Coronado, and I had subconsciously believed it and was unknowingly perpetuating it.

The photo of that 1956 Coronado High basketball team made me question many of my false assumptions, and it motivated me to embark on learning as much as I could about this previously unknown history of African Americans in our town. I now felt I owed it to my family to research and document this truth:Proud and patriotic African American families have lived here in Coronado since at least the late 1800s.

There were many questions to be answered: When did Coronado’s earliest African American residents arrive here, and where did they come from? Where did they live? What types of jobs were available to them in Coronado? What role, if any, did military service play in breaking down racial barriers in Coronado for these families?

My research took me into the photographic databases at both the San Diego History Center and the Coronado Historical Association. I also relied heavily on Ancestry.com and its powerful search engines, which include Census data (including the Slave Schedules of 1850 and 1860), City Directories, Military records, as well as Birth, Marriage and Obituary notices. I reviewed old Coronado High School yearbooks from the Coronado Library collection, and also reviewed some of the historical documents being held by the Coronado Historical Association.

The first and most pressing question that I wanted answered was: Who were the first African Americans to live in our city? The answer to that question came about by the discovery of an October 1963 story in the Coronado Eagle from a Mrs. Lucille Soaper Stites, a Coronado resident who was originally from Henderson, Kentucky:

The Early Pioneers

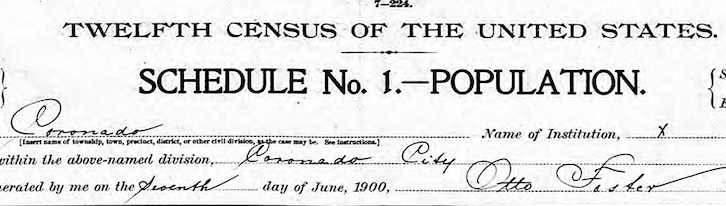

This article confirmed that African Americans were in fact part of Coronado from its founding in 1887, and that several of these families settled here permanently, including that of a man named Gus Thompson. Unfortunately, the 1890 Census records were destroyed in a fire, so the earliest Census data available to confirm the presence of these families was the 1900 Census.

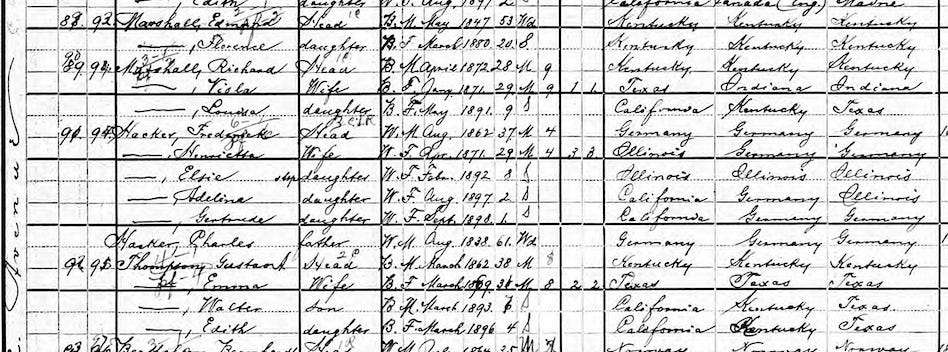

The 1900 Census confirmed there were in fact three African American families from Kentucky living in Coronado at that time (as well as a family from Tennessee):

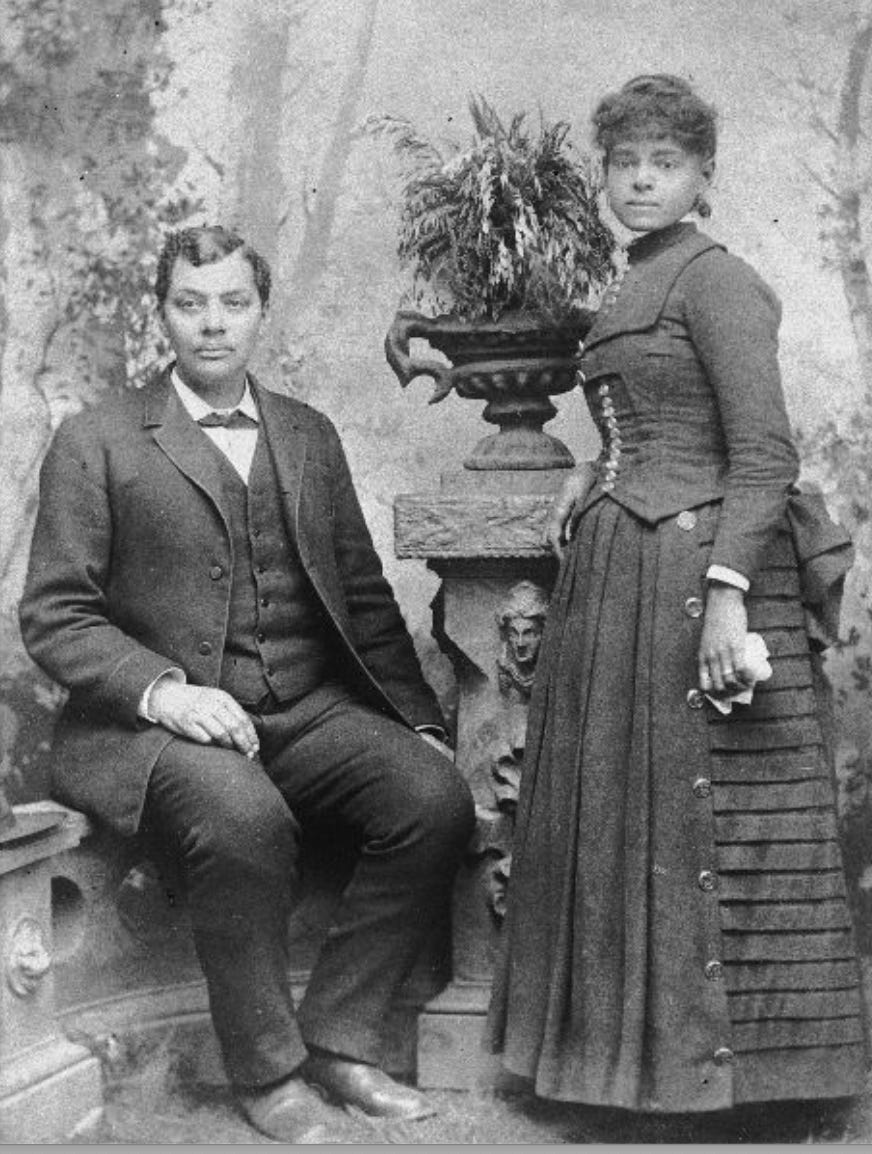

The Thompson Family - Gustavus and his wife Emma and two young children, Walter and Edith, lived on C Avenue, a property that they owned (not indicated on the 1900 census but confirmed in later Census records).

The Marshall Family - Also on C Avenue, Widower and patriarch Edmund lived with his 20 year old daughter Florence, as well as his 29 year old son Richmond, wife Viola and their young daughter Louise. Edmund owned the property, and indicates that son Richmond paid rent.

The Banks Family - George and his wife Massy and two young sons Arthur and Sammy, lived on Adella Avenue and owned their home.

The Hunter Family - Henry and Martha Hunter, age 53 and 47, originally from Tennessee, lived at on B Avenue.

As I move ahead with this project, I will be releasing individual stories taking a deeper dive into the details of the lives of these early pioneering families, and how they built “a place of their own” in the Crown City. Below is just some brief descriptions of the people I intend to cover in the stories ahead:

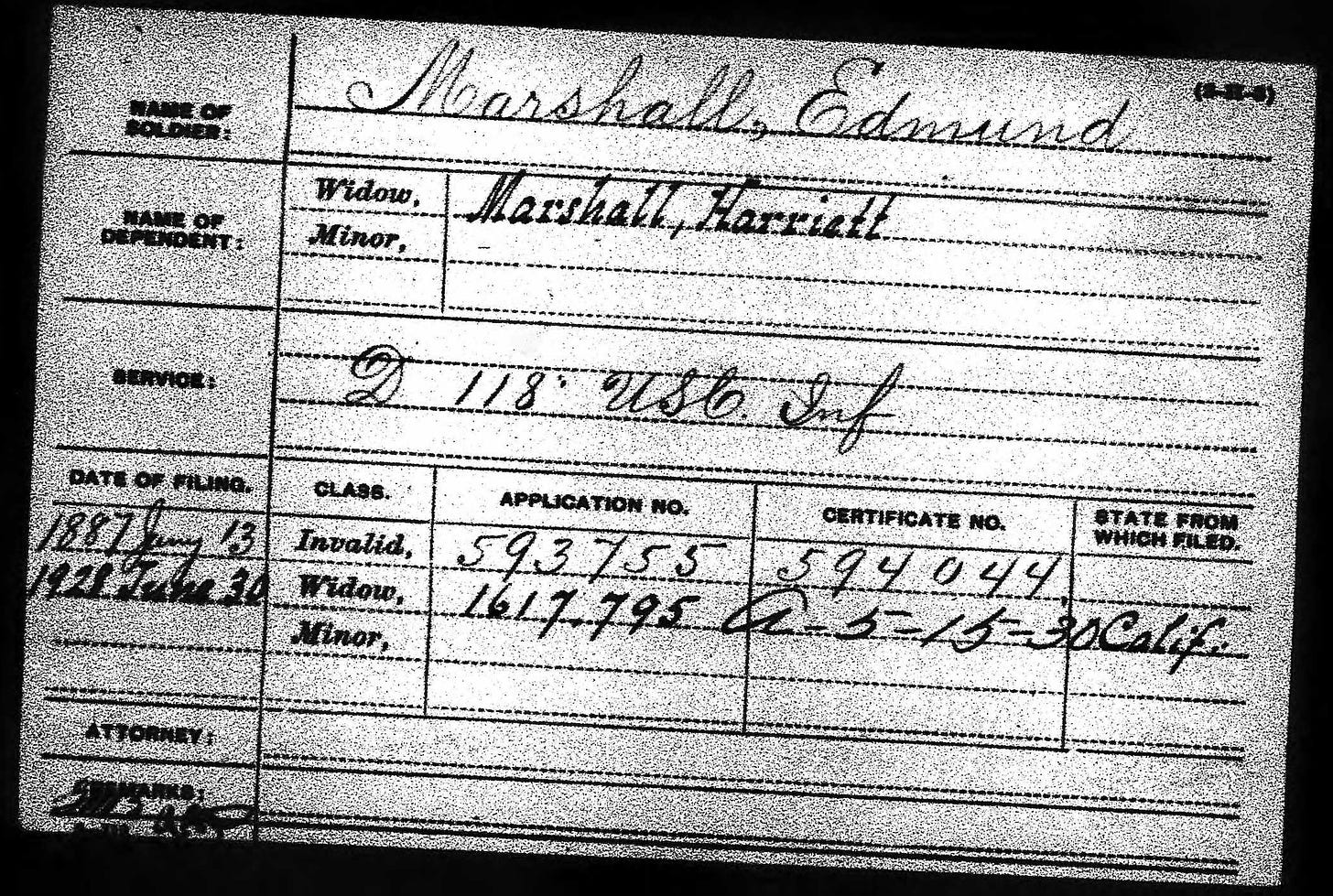

Edmund Marshall, who escaped slavery to join the 118th Colored Infantry of the Union Army and participated in the historic liberation of Richmond, Virginia, a key event that ended the Civil War.

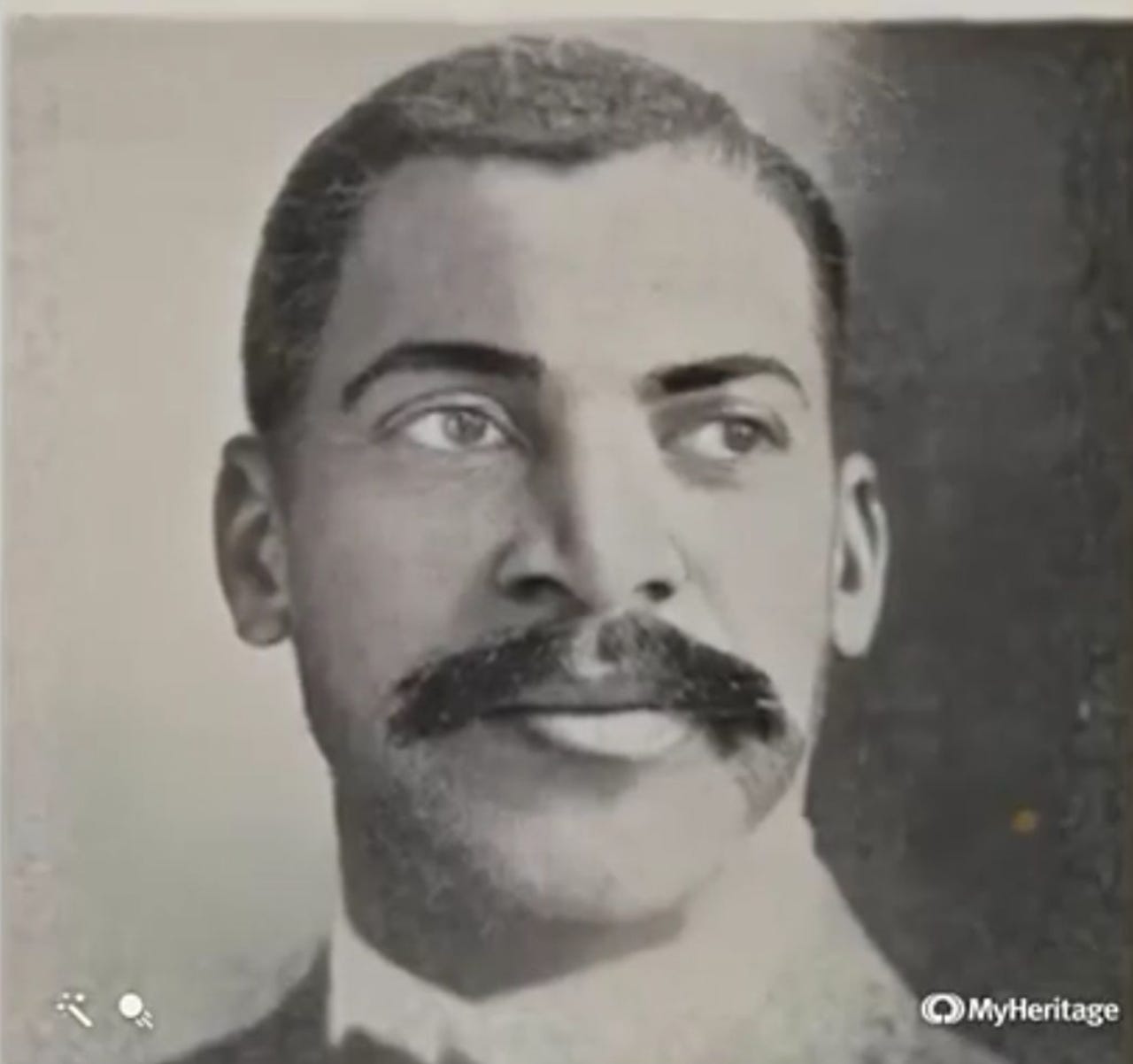

Richmond Marshall (son of Edmund) arrived in Coronado at age 14 and attended school in Coronado and later rose to prominence as a state-wide respected leader within the African American community before his tragic death in 1906.

Born into slavery in Kentucky, Gustavus Thompson arrived in Coronado in 1887 and married his wife Emma Gardner in 1894. Their incredible entrepreneurial spirit and success, as well as their civic commitment to the betterment of the African-American community in San Diego is an important story.

George and Mary Ellis: Brother-in-law and sister to Gus Thompson, would move from Kentucky to Coronado in 1910 and spend the next 29 years in Coronado.

Henry and Martha Hunter: Henry and Martha arrived in Coronado in the earliest days of its founding. Henry initially worked on the docks, but was soon hired (along with wife Martha) to be the caretaker and cook of one of Coronado’s most important yet unsung founding fathers, Charles T. Hinde.

The Hudgins Family: Arrived in San Diego in 1887 and moved to Coronado in 1905. Amos Hudgins escaped slavery in 1863 to join 2nd Kansas Colored Troops and fight in the Civil War, and later reach the rank of Sergeant as one of the original Buffalo Soldiers (1867-72). He and his entrepreneurial wife Cynthia moved from Topeka, Kansas to San Diego in 1887, before eventually moving to Coronado in 1904. Their son Algernon (a pioneer in Ham Radio and a WWI veteran), granddaughter Cynthia May and a great-grandson all resided in Coronado over the past 110 years.

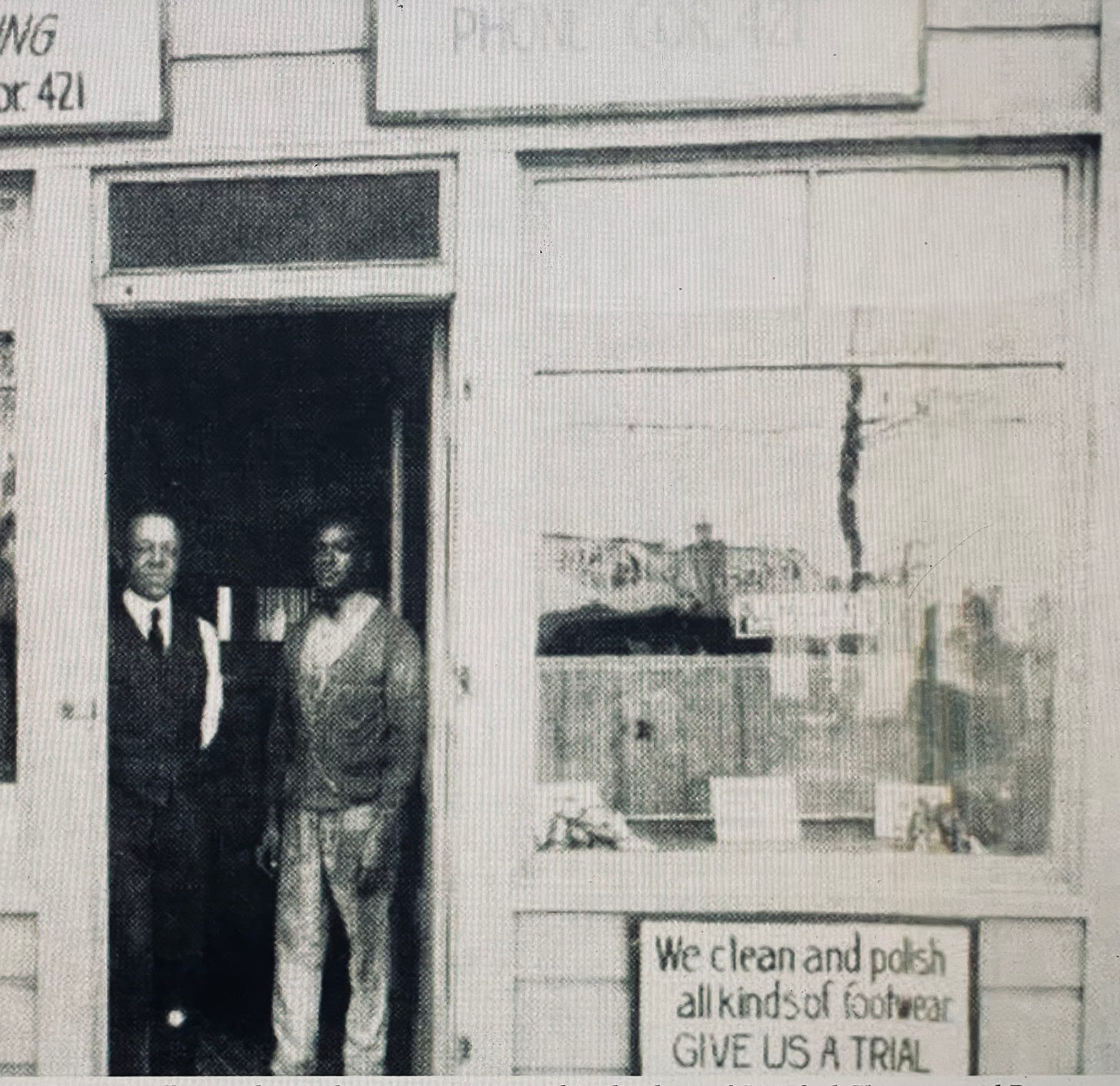

Another important family that arrived in Coronado somewhat later is The Ludlow Family, who arrived in Coronado in 1918. James Ludlow served in the Philippines during the Spanish-American War and was later employed as a chauffeur for the French Consulate in Washington D.C. shortly before the onset of WWI. He his and his wife Tallie opened Satisfied Dry Cleaners on Orange Ave and raised a large family in their home on H Avenue. Five of their six children served simultaneously as active duty military during WWII. Their grandaughter Claudia Ludlow is currently the General Manager of the Glorietta Bay Inn here in Coronado.

Much of what I have discovered in these historic documents and photos, and the historical accounts found in history books, add only a glimpse of what life may have been like for these families. There remain few first person accounts of this history, yet there is one that it is particularly illuminating, the incredibly sweeping oral history told by Cynthia May Hudgins to Barbara Palmer in 2000.

Before their arrival in Coronado, many of these pioneers were enslaved or whose parents and multiple generations of their family who had been enslaved. Some, like Amos Hudgins and Edmund Marshall, heroically escaped slavery and participated in fighting for their personal freedom and the freedom for all Americans in the Civil War.

At the end of the Civil War, these families certainly rejoiced in the establishment of the Freedmen’s Bureau to support them, as the United States attempted to turn a new leaf as a multiracial democracy during the critically important Reconstruction period. Their hopes were most certainly crushed when Reconstruction was abandoned in 1877 and was replaced by a full embrace of Jim Crow. During that time they endured the terror of Night Riders and the rise of the KKK, and it is no surprise that when the chance came, they fled to the safety and better horizons out West in California.

Some, like Gus Thompson and the Marshall family, arrived in Coronado with the support and protection of Elisha Babcock, the dynamic visionary founder of Coronado and builder of the Hotel Del Coronado. Mr. Babcock came to Coronado with his young family from Evansville, Indiana (located just across the river from Henderson, Kentucky).

The photo below represented that promise of a new future. The photo is from 1887 or 1888, from the first school in Coronado. Among the unnamed children is most likely Richmond Marshall, age 14, son of former slave and civil war hero Edmund Marshall. It is a remarkably beautiful photo, and it remains the earliest proof of African Americans being resident in Coronado.

In the stories ahead, I hope to share more about what these families left behind in places like Henderson, Kentucky, and Topeka, Kansas, and the lives they built here in Coronado. They are truly American stories which represent how far we have come as a country, and the journey that remains ahead.

Kevin Ashley, March 2022